New Insights Into the Neuroscience Behind Conscious Awareness of Choice

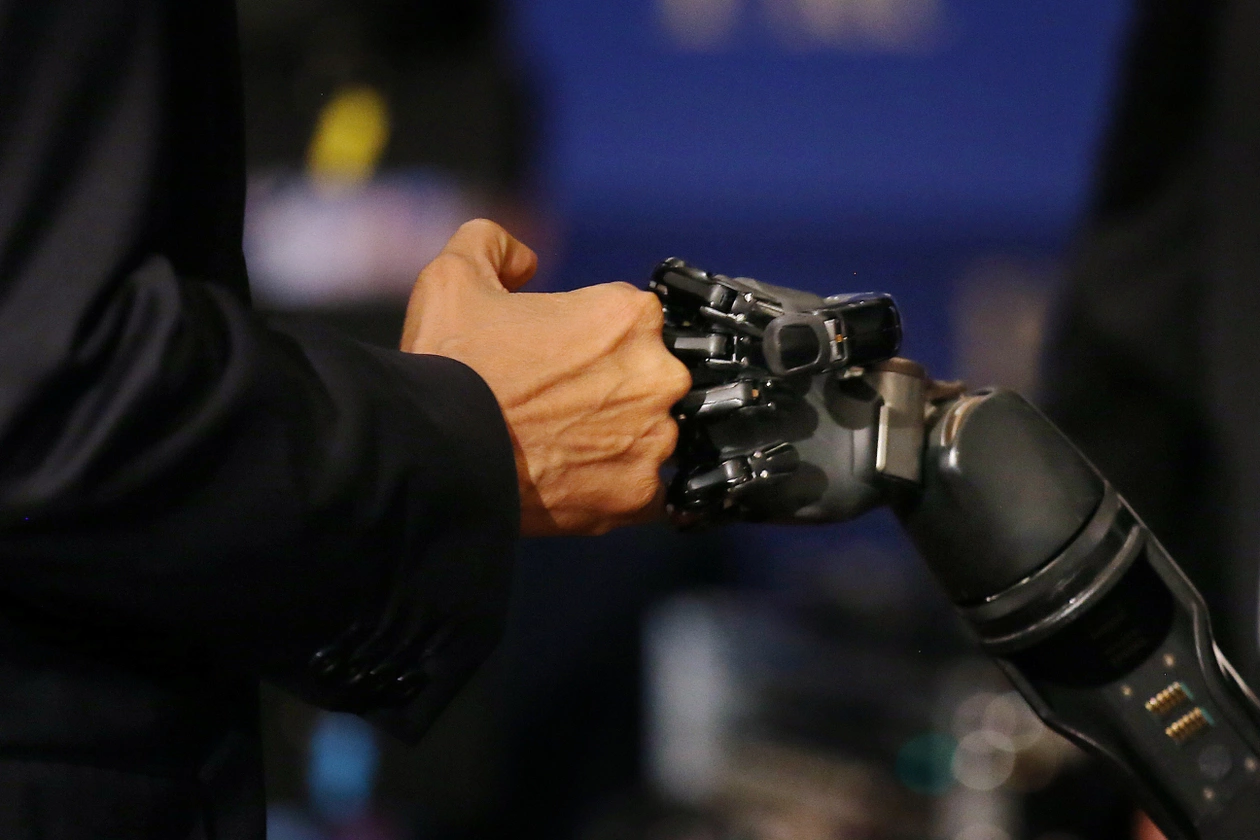

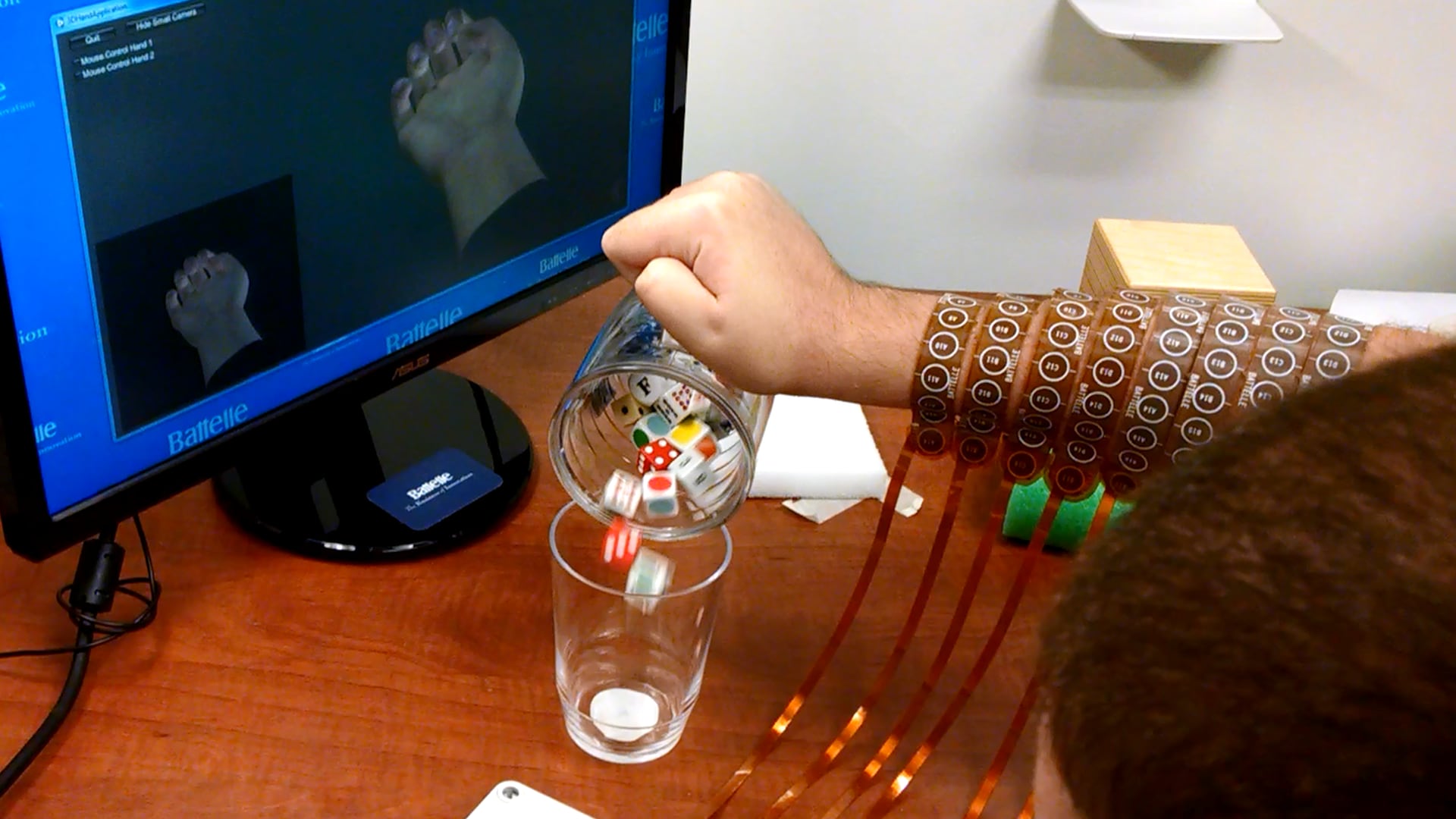

By Lori Dajose When you absentmindedly reach out to pick up your cup of coffee and take a sip, what happens in your brain? Many studies have shown that brain activity begins to ramp up even before you are aware of your choice to move. But this poses a conundrum: Do we have free will to make our own choices, if our brains are already preparing for actions before we are even conscious of them? Now, a new study from the laboratory of Richard Andersen, James G. Boswell Professor of Neuroscience, and Leadership Chair and Director of the T&C Chen Brain–Machine Interface Center, gives new insights into how the brain encodes for our choices about movement. The research indicates that brain activity of abstract high-level choices (such as the desire to consume more coffee) connects to the actual actions (such as reaching out a hand) even before the awareness of such choices to move. “The implementation of current brain-machine interfaces that read out the intent of patients assume that they are simultaneously consciously aware of the intent that is being decoded from their brains,” says Andersen. “Taking into account this early subconscious activity is critical when designing algorithms for brain-computer interfaces