By Ariana Eunjung Cha

Ian Burkhart was only 19 when the accident happened. He had been swimming in the Outer Banks with some buddies when a wave caught him and hurled him into a sandbar, leaving him paralyzed from the neck down. But he always held out hope that medical science would one day be able to help him regain enough movement to become more independent.

That day has finally arrived.

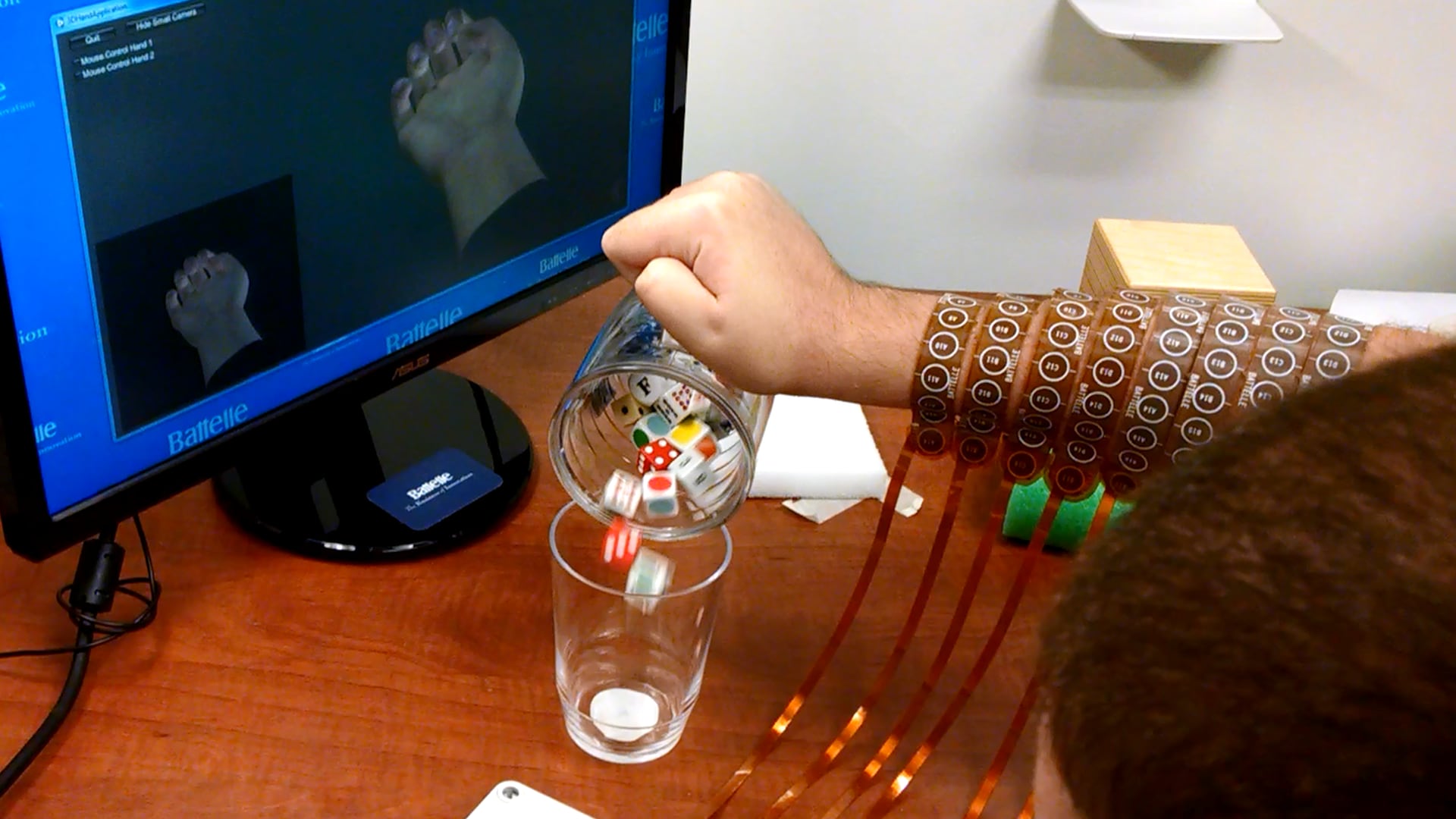

Scientists reported Wednesday in the journal Nature that they have been able to implant a chip interface in Burkhart’s brain that sends signals to an array of 130 electrodes embedded in a “sleeve” he wears on his arm that has given him the ability to move his hand with significant accuracy. Holding a glass of water and pouring it out. Using a stick to stir the contents of a jar. Playing Guitar Hero. Swiping a credit card.

These are the movements of mundane, daily life that many of us take for granted. But for Burkhart it’s nothing short of a miracle.

“The first time I was able to open and close my hands it really gave me a sense of hope for the future,” Burkhart, now 24, said in a call with reporters.

Lead researchers Chad Bouton, Nick Annetta and Ali Rezai said the effort took a multi-disciplinary team of scientists from neurosurgery to electrical engineering. The technique they used involves reconnecting the brain to the body by bypassing the damaged spinal cord.

For the interface to work, Burkhart concentrates on the movement he wants to make and a computer connected to the chip translates those signals into something his muscles understand. It turns out that each person has his or her own unique language that makes the machine a kind of “interpreter.”

The study marks the first time a paralyzed patient has been able to regain movement in his own body — a total of six different wrist and hand motions — by using signals that originated within the brain.

“We were not sure this would be possible. This result really exceeded our expectations,” said Bouton, a researcher at the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research in Manhasset, N.Y.

Burkhart tested and fine-tuned the system during up to three sessions a week for 15 months after the operation that implanted the chip in his brain’s motor cortex region. The surgery was led by Rezai, director of the Center for Neuromodulation at Ohio State University’s Wexner Medical Center.

When the doctors first broached the procedure and experiment, he was hesitant. “It was something I certainly had to consider for quite a bit of time,” he recalled.

But in the end, Burkhart said, he felt the risk was worth it because of the technology’s potential for improving his daily quality of life. “For me being in a wheelchair and not being able to walk is not the biggest thing.” Rather, “it’s the lack of independence” that comes from not being able to use his hands. “I have to rely on so many people for things.”

The breakthrough is one of a number of recent advances in brain-computer interface for paralysis. In December 2012, scientists from the University of Pittsburgh helped Jan Scheuermann, who is quadriplegic, grab chocolate and put it to her mouth with a robotic appendage. Others have been experimenting with similar treatments for people with Lou Gehrig’s disease and stroke.

Throughout the world, millions of people are living with full or partial paralysis, and the achievement marks what scientists say may be a new era in the types of treatment available to them. While the interface can only be used in the lab at this time, Annetta, an electrical engineer at the Ohio-based Battelle Memorial Institute, said their immediate goals include miniaturizing the equipment and making it more practical for patients so they can use it in their homes or out and about in their communities.

“This opens up so many opportunities now that we know it’s possible,” Bouton said.